On

the Trail of the ‘Elusive’ Lillian and Marion Morehouse*

Unraveling

the Genealogical Mysteries of the World's First Supermodel,

by

Rob Couteau.

| On

the Trail of the ‘Elusive’ Lillian and Marion Morehouse* Unraveling

the Genealogical Mysteries of the World's First Supermodel, by

Rob Couteau. |

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| While preparing to interview the E. E. Cummings’s biographer Christopher

Sawyer-Lauçanno, I became intrigued by the figure of Marion Morehouse (the poet’s

lifelong companion), or perhaps I should say by her nebulousness. In the

late Twenties and early Thirties, before meeting Cummings in 1932, Marion was

one of the most widely recognized fashion models of the day, appearing in both

Vogue and Vanity Fair. The renowned photographer Edward Steichen

called her “the greatest fashion model I ever shot,” adding: “Miss Morehouse was

no more interested in fashions as fashions than I was. But when she put on the

clothes that were to be photographed, she transformed herself into a woman who

really would wear that gown or that riding habit or whatever the outfit.” She

was also a favorite of the photographers Cecil Beaton and Baron George Hoyningen-Huene.

Two years before her death, Beaton wrote: It was not until Miss Marion Morehouse was discovered by Steichen that photographic models became so well known that they exerted an influence on the public. The aim of models at this time was to be grand ladies, and Marion Morehouse, with her particularly personal ways of twisting her neck, her fingers and feet, was at home in the grandest circumstances. These

quotations were each included in Marion’s ample, two-column New York Times

obit, “Marion Morehouse Cummings, Poet’s Widow, Top Model, Dies.” The title of

the obit could just as easily have been phrased, “First Top Model.” In

the words of Tobia Bezzola, a curator at the Kunsthaus Zürich, Steichen’s “mannequins

– even if they were not stars of stage and screen – became recognizable personalities.

In his collaboration with Marion Morehouse, he in effect laid the groundwork for

the idea of an identifiable supermodel.”* In The Model as Muse: Embodying Fashion,

Harold Koda, the Curator in Charge at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, places

the careers of Morehouse and Steichen in a broader cultural context: Cultural awareness of modeling as a respectable,

stand-alone profession was slow in coming…. [and] it was not until the mid-1920s

that the fashion model began to emerge as a fully formed social and professional

entity. One event in particular – a model search organized in New York by Vogue

in 1924 for the visiting French couturier Jean Patou – signaled, perhaps, that

society had finally recognized that fashion presentations featuring live models

not only advanced the agenda of the industry, but also provided women with viable

career opportunities. Among those discovered in the process of selecting from

more than 500 applicants hoping to join Patou’s cabine were Miriam Hopkins,

Ann Andrews, Dorothy Smoller, Lily Tosch, and Marion Morehouse – the latter, though

not selected by Patou, was certainly noticed by Vogue and would appear

to have been chosen by fate. With Morehouse’s meteoric ascent, America witnessed

the beginning of the model’s rise to international fame and eventual influence

upon feminine beauty and popular culture. Confident, emancipated, and unapologetically

liberated, Morehouse’s image was as fresh and exciting to the young sophisticates

of the 1920s as it was alarming to the old establishment. When Edward Steichen

was hired at Vogue in 1923 to replace [Adolphe] de Meyer, his innovative

modernist photographic style ripped through twentieth-century visual culture like

a searing knife. Almost overnight, de Meyer’s painterly pictorialist images were

thrust into the past as Steichen introduced the twentieth century to the modern

woman by way of unerring clarity and his favorite model – Marion Morehouse. Embodying the adventurous and self-directed

lifestyles celebrated in magazine and novels of the era, [model Lee] Miller and

Morehouse in many ways symbolized the fully realized, progressive attitudes of

the 1920s. Living examples of the newly liberated modern American woman, they

put a face on a generation intent upon turning their backs once and for all on

still-lingering Victorian sexism and the last gasps of Edwardian propriety – sentiments

that fashion (no matter how high hemlines might rise) could only hint at. Doing

much to temper the more frivolous connotations of the out-all-night, free-spirited

flapper, Marion Morehouse and Lee Miller – with their cool, nonchalant elegance

and confident, unaffected smiles directed right into the lens – projected refreshingly

frank and fearlessly modern attitudes, and heralded not only changes in fashion,

but also a new way of living for American women.* Koda’s

book was published in 2009 to coincide with the exhibit “The Model as Muse,” featured

at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. More recently, a September 2010 article by

Robin Muir in FirstFT magazine, “Vogue’s Earliest Celebrity Models,” expanded

on this theme: That models became so recognizable that they began to fascinate the public

is often traced back to Marion Morehouse. And with justification. She was not

an actress or a society figure but something new entirely, a dedicated model,

and Vogue began to use her name in credit lines.* Yet Marion had managed to cloak so many

details of her personal life for so many decades that Cummings’s previous biographer,

Richard Kennedy, had at times clearly thrown his hands up in exasperation. In

an essay titled “The Elusive Marion Morehouse,” he complained of “a great many

obstacles” that were placed in his way while working on his thirty-year project,

adding: “The principal obstacle was Marion Morehouse herself.” This was the case

even more so when the subject was Marion instead of Cummings: “Whenever I would

ask her a specific question about some feature of her life, she would raise a

warning finger against my inquiry…. It was not until after her death that I was

able to begin my real biographical research.” Kennedy adds: “My gathering of information

about her had to start with the facts set down in her obituary, a course that

gradually raised questions in my mind about the persona she had created for herself

during her lifetime.” Indeed, one glance at her Times obituary reveals

several key errors that took root as a result of these obfuscations, the biggest

one being the year of her birth. Kennedy himself was suspicious on this score:

“In Edward Steichen’s photograph of her, made for Vogue magazine in 1925,

she was supposedly only nineteen years old; yet she looks much older.”* Unable to track down a March 9, 1906 birth certificate for Marion in

South Bend, Indiana, Kennedy also failed to find one for 1905 or 1904. As I would

soon discover, even if he’d gone back another year, to 1903 – the actual date

of her birth, according to census records I eventually unearthed – he still would

have come up empty handed, at least in South Bend. A county clerk with whom I

recently spoke said that birth certificates were not legally required in Indiana

until about 1906 or 1907, so most of the “home births” (the majority of births

in the state, at that time) remained unrecorded. Marion’s obit also erroneously

reports that she and Edward Estlin Cummings were married and that Marion attended

St. Anne’s Academy in Hartford: a school that, according to Kennedy, never even

existed. Almost twenty-five years had passed since

Kennedy’s Dreams in the Mirror:

Biography of E. E. Cummings had first

appeared. As an avid genealogist, I realized that online resources for family

research had snowballed into tremendous proportions in just the last ten years.

Thus, when Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno’s E.

E. Cummings: A Biography was published in 2004 – a lyrical and informative

work that successfully builds upon Kennedy’s foundation – much of this genealogical

material still remained unavailable. When I contacted Christopher in July of 2014

and raised the possibility of finding something new, he enthusiastically gave

me his blessing to start digging. What followed in just the next few hours

was one of those uncanny serendipities that resonate with the allure of a Sherlock

Holmes episode. First, I had a look at the obit that had sent Kennedy on a trip

down the rabbit hole. As a genealogist, my eye instinctively lingered on the names

of the other family members mentioned therein: a sister, Lillian, who had refused

to speak with Kennedy after Marion’s death, leading him to “wonder about what

family secrets were being protected,” and a brother, Benjamin. Logging into “Ancestry.com,” after a search for a family tree on Marion yielded nothing of note, I tried to find something on Lillian. (Although Marion was included in most of the E. E. Cummings pedigrees, none revealed the names of her parents or anything of interest about her background.) Then I stumbled upon a lodestone. A listing for “Lillian Morehouse Cox” appeared on Ancestry, and it was cross-linked to a web site that I’d found helpful in the past. “Find-a-Grave.com”

revealed that Lillian was buried in a cemetery in Bloomfield, Connecticut, along

with several other Morehouses. (The site allows members to erect online memorials

for the deceased, including vital statistics and photographs.) And

a memorial for Lillian contained three amazing portraits. One was a snapshot taken

of Lillian, her brother Benjamin, and her mother, who appeared to be in her seventies.

The other two photos were professionally composed. One was captioned, “Lillian

modeling circa 1920s,” and it featured a tall, slender, willowy figure wearing

a satin dress with a matching cape, with her bobbed hair cut short in the style

of the flappers. The last picture was the most amazing of all: the bust of an

beguiling young woman, perhaps eighteen to twenty years old, with pale, opalescent

skin, an oval face, full lips, a prominent nose, long flowing hair, and an utterly

entrancing expression as she gazes off, into the distance. The caption reads:

“Actress Lillian Morehouse Cox.” None

of these intriguing images had ever appeared in print. In addition, Lillian’s

birth was listed as March 31, 1906: the same month and year that her sister, Marion,

claimed to have been born. Although Richard Kennedy had expressed doubts about

the family actually hailing from South Bend, the memorial states that Lillian

was indeed born there – and that she was the “daughter of Benjamin and Anna Morehouse.”

When I shared this information with Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno, he excitedly

confirmed that the names of Marion’s parents had never been known to any of Cummings’s

biographers. And there was no doubt the memorial was referencing the same family.

A bio on Lillian said she was The sister of Marion Morehouse Cummings, the

wife of poet e. e. cummings. Also a brother Benjamin Morehouse. Lillian was a

model and stage actress. Lillian was married on August 3, 1928 to Alan B. Cox

in New Jersey. They divorced in June 8, 1942 in Miami, Florida, St. Joseph County. An additional note indicated that the memorial

was created by one Tony Ungaro on February 16, 2009. Just as I’d suspected, all

this was relatively new information. With these crucial facts in hand, I returned to Ancestry and began to dig up additional data. Most importantly, I located Lillian and Marion in a 1910 U. S. Federal Census taken in Connecticut, which shows that Marion was then seven years old and was born in Indiana to “Annie” Morehouse. Lillian’s age was off by a year: on April 15, 1910, she was actually four years old, but the enumerator has written “3.” (Her birth in 1906 was later confirmed by her death certificate.) The census also includes their brother, Benjamin, who was two, thus born in 1908. The family was then living at 20 Centre Street, in Hartford. Although it said Anna was married, her husband wasn’t listed along with the rest of the family. Instead, “Benjamin I. Morehouse” appears in the 1910 census recorded in South Bend, living at 810 North Lafayette Street with his seventy-four-year-old father, John Morehouse, his sixty-four year old mother, Elizabeth, and three of his younger siblings. According to this document, he’s married; and under a column headed “Number of Years of Present Marriage,” the enumerator has written “7.”* I

next contacted a clerk named “Chuck” at the Mount Saint Benedict Cemetery. A brief

telephone conversation confirmed the accuracy of the memorial data and revealed

that Lillian was buried in the same plot as her brother, Benjamin Jr, and Anna

Shortell Morehouse, their mother, who died in 1965. Anna’s husband died first,

in 1954, and he was buried with Anna Halpin, Anna

Shortell’s mother, in another part of the cemetery. An

obituary in the online Hartford Courant newspaper states that “Lillian (Morehouse)

Cox, of Hartford, died Tuesday (May 31, 1994) in Hartford Hospital. She was born

in Hartford, daughter of the late Isaac and Anna (Shortell) Morehouse.” Another

edition of the paper, published on May 28, 2000, featured an article about local

celebrities and people of note who are interred in the vicinity. Titled “The Sweet

Hereafter,” it features these consecutive paragraphs: Isaac Benjamin Morehouse (1870-1954), Mount

St. Benedict Cemetery, Bloomfield. He was an actor on the vaudeville stage. Lillian

M. Morehouse (1906-1994), Mount St. Benedict Cemetery, Bloomfield. She was an

actress and model, and the sister-in-law of e.e. cummings. As I would eventually discover, the reversal of Mr. Morehouse’s first

and middle name appears throughout his life, and on several key documents, such

as his first marriage certificate and his death certificate (the latter lists

Lillian as the “informant”). On his son’s birth certificate, under “Father’s Name,”

the clerk had initially typed “Isaac,” but then he crossed it out and replaced

it with “Benjamin.” After

spending the next few days collecting additional information and constructing

a basic family tree, I contacted Tony Ungaro via e-mail. I explained that I was

preparing to interview Professor Sawyer-Lauçanno, and that I hoped we could speak.

A genial former executive from Hartford, Tony telephoned the following day, on

August 5, 2014. And he had quite a story to tell. Tony was formerly employed as an executive

for the Heublein Corporation in Hartford, where Lillian Morehouse worked in a

clerical position. (“We manufactured A1 Steak Sauce, Smirnoff Vodka, and Grey

Poupon mustard.”) During this period, Tony had no idea that Lillian was related

to the wife of E. E. Cummings. Although they didn’t know each other that well,

he would occasionally “help her out with a ride home from work,” for which she

was quite grateful. After

thirty-four years at Heublein, Tony retired in March 1994, his last position being

Manager of Period Cost Control. (“I developed and managed ninety-million dollars

in budgets.”) Four months later, he moved with his wife to Sarasota, Florida.

After Lillian passed away in May of that year, he received a probate letter from

her lawyer in West Hartford, which informed him that Lillian had remembered him

in her will. Quite surprised by all this, Tony replied that he didn’t want any

money – but that he would be happy to receive some mementos. Shortly

afterward, a UPS truck delivered three large boxes containing letters, photographs,

and divorce papers. There were also “photo albums going back to the 1800s, and

many very personal letters,” including some that had been exchanged between Lillian’s

parents. As we spoke, Mr. Ungaro remained eminently discreet about the contents

of some of these letters. “The mother and father experienced serious difficulties

and were separated for a time,” he said, but he didn’t get any more specific than

that regarding the contents of these missives – and I didn’t press the matter.

He added that many of the letters exchanged between Anna and Benjamin were so

personal that he decided to destroy them. When we spoke a second time, about seven

months later, he was more specific: the letters concerned great financial hardship,

and the separation he was referring to occurred in the Thirties, when Lillian

was in a hospital in New York. (More on this later.) This dovetails with the contents

of the 1930 U. S. Federal Census, which shows that Benjamin was married and living

with his mother, Elizabeth, at 302 Hawthorne Drive, in South Bend. Anna doesn’t

appear in the census, although a city directory from this period says that she

officially resided at the same address. Therefore, she may have been in the hospital

during this period. Retaining

only a small file of mementoes for himself, the remainder he forwarded to a relative

of Lillian’s that he tracked down in Indiana.

Tony constructed a pedigree based on what he’d found in the family documents,

which he emailed me that same day. This allowed me make rapid progress in assembling

an even broader genealogy. When

I asked if there was anything else of note in the boxes, Tony said there were

a few small pieces of artwork, including pastels, which were created by Cummings

and which he also sent to Lillian’s relative. (Early in his career, Cummings was

a well-respected visual artist; and besides composing portraits of Marion he continued

to dabble in the arts later in his life.) Attached to the pedigree that Tony had shared

with me were a handful of photos of Marion and her family that have never appeared

in public before. The first was a head shot of Lillian’s father, Benjamin I. Morehouse,

whom Tony referred to as “Isaac.” Tony said that the letters and memorabilia also

revealed that “Isaac was a vaudeville actor who was “known for his ability to

go from ‘black face’ to white in just minutes.” An oval-shaped portrait, the photo

appeared to be printed on a flier or publicity sheet of some sort, with lettering

embossed on the paper beside it. (Although the image I received was cropped, the

letters “BE” – perhaps the first two letters of his name – appear to the right

of the picture). Tony’s photo archive also gives us an intimate look at the other

members of the Morehouse family, and it includes the only known image of Marion

posing with her sister, which appears to be the earliest extent photo of Marion.

In the family tree that Tony created, there

was also a note regarding a nuptial ceremony of some sort that had occurred between

Benjamin and Anna in a church in the Bronx. When I remarked that this was “well

after the birth of their children,” Tony said it “may have been after the fact,”

but that, given the difficulties experienced by Anna and Benjamin, “nothing would

surprise me.” I later contacted the church and obtained a record of this event,

which proved to be a marriage. I should add that there was no other record of

their marriage in any online database, and the church’s files from this period

were not digitalized. If Tony hadn’t inherited Lillian’s papers, I doubt anyone

would have found a trace of this event, especially since there was no clue that

the couple might have remarried ten years after the birth of their last child. Lillian had bequeathed Tony $10,000 (of

which he received $4,000), and she willed her doctor $40,000. She also left money

to her two caretakers. She’d amassed about $280,000, which utterly surprised Mr.

Ungaro, since she was employed merely as a clerk. But he added that, after Marion

died, the copyright of Cummings’s work went to Lillian, to the chagrin of Cummings’s

daughter (Nancy Thayer). Much of this had been depleted, however, by medical care

for her and her brother, Benjamin, so the amounts received by those in the will

were “less than specified.” Tony was amused by the fact that, when Lillian’s doctor

eventually moved to Chicago, “she was angry at him for leaving her.” When I noted

that Lillian hadn’t left anything to her distant relatives, he concluded that

this was probably due to their estrangement. Mr. Ungaro struck me as a completely trustworthy,

thoughtful, and down-to-earth fellow. During our conversation, I could hear his

wife occasionally speaking in the background, adding whatever she could to help

trigger his memory. Although he was aware of the famous poet and his work (“E.

E. Cummings wrote with those little letters, you know?”), he remained more interested

in Lillian and in carefully preserving her memory. I respected his decision to

honor the privacy of Lillian’s parents but, at the same time, to be as helpful

as possible while doing so. In

the months ahead, each of Mr. Ungaro’s leads checked out. I was able to obtain

various birth, marriage, and death certificates that verified his claims, and

I eventually managed to extend the genealogy of both Anna Shortell and Benjamin

Morehouse back a generation. I also located Anna and Benjamin’s death certificates,

which list the names of each of their parents, thus confirming Tony’s pedigree

data. City directories from Hartford and South Bend reveal precise locations where

they lived, and they also chronicle Benjamin’s various professions. Census results

from Indiana, New York, and Connecticut helped to fill in other gaps. By the fall

of 2014, I was able to reconstruct much of the background of Marion, Lillian,

and their antecedents. These are some of the main events: • According to the 1910 and 1930 census,

Marion Morehouse was born in Indiana in 1903. The 1910 census, taken in Hartford,

reveals that her mother, “Annie Morehouse,” was married and was the head of the

family. Note the absence of a husband in this listing, who would normally be considered

as the head. Strangely enough, under a column for the “Number of Years of Present

Marriage,” the enumerator has left the space blank, although it’s filled in for

each of the other married couples on the page. Perhaps this indicates a separation

just two years after the birth of Benjamin Jr. • In the 1930 census, taken when Marion

was twenty-seven, she was living on her own, renting a room at 5 Prospect Place,

in the Bronx. Although the original building is no longer there, it must have

been a high-rise, as there were 334 other “households” at this address. The enumerator

notes Marion’s “Occupation” as “Actress,” her “Industry” as the “Theatre” (spelled

the European way). Under “Class of Worker,” she’s considered a “Wage or salary

worker.” We also learn that she lived without a radio. • Apparently, Marion didn’t start fibbing

about her age to the census takers until 1940, when she informed an enumerator

that she was born in 1918, making her twenty-two instead of thirty-seven

years old. (Oddly enough, 1918 is the same year that her

parents remarried.) One wonders if E. E. Cummings was standing within earshot

and Marion was merely propagating a myth that even her lifelong companion had

remained unaware of. Upon learning this, Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno remarked

that, all along, he had the impression that Marion kept many things a secret from

Cummings. “My sense,” he said, “is that he didn’t know much of any of this.” (Of

course, one must also allow for the possibly of a simple error on the part of

the enumerator, which was common.) Although Marion’s surname is misspelled (“Moorehouse”),

it’s undoubtedly her, for it correctly lists her address as 4 Patchin Place, the

small mews where she and Estlin Cummings maintained separate apartments for many

years. (Cummings first moved into 4 Patchin Place on September 8, 1924.) And consistent with the 1910 and 1930 census results, it records

her birthplace as “Indiana.” Under “Marital Status,” it says that Marion was single.

Her occupation is “Model,” her industry is “Artist Model.” Under “Highest Grade Completed,” we read: “High

school, 4th year.” This is contradicted by the 1930 census, which indicates, under

“Attended School,” “No.” But the 1910 census, taken when she was seven years old,

shows that Marion was then enrolled in elementary school. • One of the family secrets that may have

led to the creation of those “walls of mystery” that Kennedy says “surrounded

the facts of Marion’s early life”* was that she was apparently born out of wedlock. In March 2015, I discovered

that Benjamin Isaac Morehouse was previously married to Etta C. Harger (née Van

Dalson), on December 22, 1889. About fourteen months later, Etta, also known as

“Nettie,” gave birth to a son named Otto Morehouse, in February 1891.* And on February 26, 1902, “Nettie” and Benjamin were divorced. In 1903 Marion was born, and the following

year Benjamin married Marion’s mother, Anna Shortell, on June 30, 1904. The ceremony

was held in the neighboring state of Michigan, in Niles: about eleven miles north

of South Bend, Indiana. The marriage registry in Niles also includes the names

of the bride and groom’s parents; and it shows that, while Benjamin was residing

in South Bend, Anna was then living in Hartford. Under “Profession,” we learn

that Benjamin Morehouse was a “Showman.”* Another intriguing detail: the “Person Performing

[the] Marriage” bears the same surname as Benjamin’s mother: Justice of the Peace

W. I. Babcock. Further research revealed that his full name was Washington

Irving Babcock, a fifty-one-year-old resident of Niles. One of the witnesses to

the ceremony, Ruth (Hitchcock) Babcock, was Washington Irving’s wife. They were

each born in New York State in the 1830s and later emigrated to Niles, where Justice

Babcock also worked as a lumber dealer. How (or if) he is related to Benjamin’s

mother, Elizabeth Jane Babcock, remains unclear. But if he is related, it might

explain why Niles was chosen for the marriage ceremony. • When I subsequently rechecked the information

on the 1910 census for Benjamin and Anna, I noticed that, under “Marital Status,”

the notation “M1” appears beside Anna’s name; while Benjamin’s status is “M2.”

I then realized that the digits referred to their number of marriages,

thus showing Benjamin to be married twice. Yet, Benjamin’s enumerator has written

“7” under “Number of Years of Present Marriage,” even though the census was conducted

about two-and-a-half months short of their sixth wedding anniversary. • Earlier in his life, Benjamin lived

and worked mostly in South Bend, but he appears in Hartford during the years 1911

and 1912 and from 1945 to 1954.* Besides working as a vaudeville actor and a scenery setter for the theater,

Benjamin was employed as a carpenter and worked in various other working-class

positions: wood finisher, paper hanger, painter for the Studebaker Corporation

(manufacturer of the Studebaker automobile; the company was based in South Bend

and was founded by two local blacksmiths), stage hand, night porter, watchman,

janitor (during the Great Depression), maintenance man. (This despite Marion’s

tendency to pose as an aristocrat.)* The 1930 census shows that Benjamin received no schooling and that his

parents (John Morehouse and Elizabeth Jane Babcock) were each born and raised

in Indiana. Civil War records note that a “John Morehouse” was “enlisted in the

Indiana 11th Light Artillery Battery on 17 December 1861 and mustered out on 7

January 1865,” although it’s unclear whether this was the same person. John married

Elizabeth Jane in June 1865, and he fathered seven children, of which Benjamin

was the third. • Marion Morehouse’s mother, Anna Shortell, was born in Hartford, as was Anna’s father, William. William’s parents, John Shortell and Mary Berry, were from Ireland. William’s wife was named Anna Halpin, and she hailed from London. Her father, William Halpin, was also born in England; and his wife, Elizabeth Dryden, was from Ireland. Hence, the Anglo-Irish cast of Marion and Lillian’s appearance. • Marion’s parents married each other a second time on December 20, 1918, in the Church of St. Francis de Sales, on East 96th Street in the Bronx. Although there’s a record of Benjamin’s divorce from his previous marriage, there’s no record in the South Bend county clerk’s office of a divorce between Benjamin and Anna Shortell, so it's possible that their 1918 marriage was simply performed as a religious ceremony. Since Anna and Benjamin both vanish

from Indiana and Connecticut directories around this time, there remains a strong

possibility that the family relocated to New York. I could find no trace of Benjamin

in Indiana or Connecticut directories from 1913 to 1924; while Anna disappears

from these listings between 1915 and 1927. A 1927 Hartford directory notes that

a Benjamin and Anna Morehouse were “removed” from the directory after a relocation

to New York City, but it’s uncertain as to whether this is the same Morehouse

couple. But they eventually returned to Indiana, and, according to a 1928 South

Bend city directory, were living at 128 North Lafayette Street. Marion

could have attended school at St. Francis de Sales (in 1918 she was fifteen years

old; Lillian twelve; and Benjamin Junior eight), since at that time the church

hosted a school. Although Kennedy has conjectured that Marion and Lillian came

to New York on their own in the Twenties in order to break into the theater, it

may have been a family relocation that first brought them to Manhattan. • Marion performed on the Broadway

stage as early as 1923, at the age of twenty; Lillian in musical revues in 1925,

when she was nineteen. Thanks to the online Playbill

Vault and the Internet Broadway

Database, we know that Marion acted in at least five

Broadway plays between October 1923 and January 1931, which ran for a total

of 412 performances. (Kennedy says Marion “was able to get jobs as

a showgirl in one or another of the musical revues such as the Ziegfeld Follies

or to find bit parts here or there in plays,” but the only play he mentions by

name is “Gilbert Seldes’s adaptation of Lysistrata in

1930”: Marion’s fifth Broadway production, which ran from June 5, 1930 to January

1931.)*

The records also show that Lillian

performed in two musical revues,

Earl Carroll’s 1924 and 1925 Vanities (a competitor of Ziegfeld), and a

musical comedy, Lucky, with a total of 403 shows between September 1924

and May 1927.*

(Lucky was featured at the New Amsterdam Theatre, which also hosted the

Ziegfeld Follies.) But since the archives contain only Broadway shows,

there may have been other, Off-Broadway productions that featured the Morehouse

sisters: a possibility that’s bolstered by Tony Ungaro’s comment that Lillian

and Marion “appeared together on the stage” (see below). The earliest Steichen photo of Marion

that I’ve seen so far dates from 1924 (see below): the same year that Marion was

discovered by Vogue during a model search organized for Jean Patou. Since

Steichen frequented the theater and the burlesque, it’s possible the famous photographer

also saw Marion perform in one of her early dramatic plays. For example, on December

26, 1923, Marion appeared in This

Fine-Pretty World at the Neighborhood Playhouse, at 466 Grand Street. After

thirty-three shows, it closed in January 1924. And later that year she

performed in a play called “The Saint,” which opened on October 11, 1924, at the

Greenwich Village Theatre on Seventh Avenue South, near Christopher Street, in

Cummings’s neck of the woods. After seventeen performances, it closed that same

month. Steichen also might have encountered Marion at the Ziegfeld Follies

or in some other musical revue.*

Kennedy says that Marion’s tall, lanky figure made it difficult for her to find

theatrical parts, but it was perfect for the role of a “showgirl.” His 1978 interview

with Marion’s friend Aline Macmahon seems to have been the source of this information:

“Because Marion was very tall,” he writes, “she

had a hard time finding roles to play on the stage, although her height and beauty

were very suitable for work she secured as a showgirl in the Ziegfeld Follies.

Lillian, an attractive blonde, was also a showgirl for Ziegfeld.”*

When I mentioned the Ziegfeld Follies to Tony Ungaro, however, he said

he could recall no evidence of their employment with Ziegfeld in the papers he’d

inherited but added that his memory was fuzzy when it came to the names of particular

shows. Although the Playbill Vault has a complete archive of opening-night performers

for the Ziegfeld Follies from 1907 to 1957, neither Marion nor Lillian

appear there. Still, there’s a possibility they were hired as replacements later

on, after opening night. Although

Marion claims to have met Cummings following her performance in a play on June

23, 1932, she never revealed the title of this production to Kennedy: a highly

suspicious omission. If they met after a Ziegfeld Follies-type of revue

(Cummings was known to use dance hall-related material in his poetry), perhaps

Marion considered such a venue to be lacking the glamour of the more “artful”

theater. In keeping with her flamboyant persona, she may have felt the need to

embellish upon this legendary encounter with one of America’s most well known

poets. However, all this remains speculative. •

Benjamin Isaac Morehouse’s death certificate lists one of the causes of his demise

as “rheumatoid arthritis”: a malady that can be passed along genetically. Therefore,

Marion, who suffered terribly from this debilitating illness, may have inherited

it from her father.

* * * Something

that cannot be captured by mere vital statistics is the effect that Marion had

upon the heart and soul of the poet. When we finally conducted our interview on

February 2, 2015, I asked Christopher to describe her relationship with Cummings

and to elaborate on how they supported each other emotionally and artistically.

“That

story,” he replied, “begins with two other relationships before that. The first

woman he falls in love with is Elaine, who was married to his friend Scofield

Thayer. Scofield, as we know now, and as I’m sure Cummings knew at the time, was,

if not ‘bi,’ gay.” “And

very much in the closet for a while.” “Yes.

An esthete, but not particularly interested in his wife sexually. Cummings falls

head over heels in love with Elaine, with Scofield’s wife. And Elaine herself

is upper-crust. She’s not the easiest person in the world to get along with; nor

was, I think, Estlin himself. But basically, they have an affair, and she gets

pregnant with Cummings’s child. Thayer, being Cummings’s best friend, knows what’s

going on, but he adopts the child – or rather, he allows it to be born as if it’s

his daughter. Eventually, Elaine and Thayer are divorced. Elaine marries Cummings,

and it does not last very long. There are just too many differences between them.

The daughter doesn’t realize at the time that she’s his child: that Cummings is

her real father. They part ways; Elaine goes off to Ireland, and Cummings is bereft.

I mean, he’s absolutely bereft that Elaine has fallen in love with someone else

and left him after he was hoping that this was going to be the love of his life. “For

all of Cummings’s ‘sexual identity’ as a poet – because he certainly has one because

of all the erotic poems, and being one of the first to write poems that were unabashedly

not just about love, but about sex – people think he must have had a million women. Well, he didn’t.

He had only three principal women.

And they were each enormously important to him. He was a very tender, very sentimental,

and, in that way, very ‘son of his father’ old-fashioned man. Then he hooks up

with Anne Barton, who is a flapper and totally unfaithful from the moment they

get together, and this kills Cummings as well. “He

loves women as women, and I’ll try to clarify what I mean by this. He enjoyed

being in women’s company. Probably among his closest friends was Hildegarde Watson,

who was married to his friend James Watson. I don’t believe there was ever a sexual

attraction on either’s part, but he absolutely adored being in her company. He

adored women. He enjoyed who they were. He enjoyed the way they smelled

[Laughs]. He enjoyed the way they looked, the way they walked. And so, in a pretty

tough period for Cummings – financially, he’s not doing well; he never did well,

and his mother generally supported him most of his life – but here he is, a ‘two-time

loser’ if you will, and suddenly here comes this angel out of the fog, Marion

Morehouse. She is young. She is, unlike Elaine or Anne, really interested in being

with Cummings.” “And

not a gold digger, like Anne.” “Not

a gold digger like Anne was, certainly. And so, she is gorgeous, and she makes

it pretty clear, pretty early on, that what she wants to do is take care of this

great man. And, wow! [Laughs] He’s finally found the love of his life.

“Who

knows what takes place in those kinds of circumstances? But clearly, there was

a tremendous attraction. I didn’t write this, because I didn’t have enough evidence,

but, from the little that I could glean, he was attracted to her initially because

she was so gorgeous. It was certainly a major physical attraction. I think it

took a while for him to let his guard down so that he could see her in a larger

way. He kept her at a distance, initially; he wasn’t quite sure of what to do.

“And

so, what we have is hundreds of pages of writing about Elaine, maybe a hundred

or so pages about Anne, but we have only about twenty pages about Marion. Why?

Because he doesn’t have to exorcise the demons. What he’s doing with writing about

Elaine and about Anne is trying to exorcise those demons. Because he wrote everything

down; he was compulsive about trying to think on paper. You could see the guy

pacing about the room, smoking endless cigarettes, then writing something down

to help him try to analyze things. Once he meets Marion, this goes away. He writes

about other things, but he’s not obsessing about his relationship any longer.

And that, in a way, tells you how perfectly matched they were. “What happened as they spent more

time together … I would say she became much more of a ‘gatekeeper’ for Cummings.

Allen Ginsberg told me a story: He’d gone to Cummings’s house and knocked on the

door, and no one answered. And he’d written him a letter and sent him a copy of

“Howl.” He really wanted Cummings’s approval; it was enormously important to him

for some reason. He finally gets to Patchin Place again, on another occasion,

and he knocks on the door, and Marion comes down the stairs, takes one look, and

says: “You. Go away. And never come back.” He tries to explain

who he is, and she just … She was the gatekeeper. And that was very much

a part of her function in later years. And with Cummings’s blessing, because he

became more of a curmudgeon as he got older. And by ‘older,’ I mean fifty-five.

The man didn’t live all that long. And she became ‘the one you had to get through.’ “I believe her political views really

began to affect Cummings’s. She was very much a right-winger. At that time, Lindberg

was on the radio, and various other right-wing isolationist, “Keep Out of World

War Two” folks. And she would get Cummings to listen to these broadcasts, because

these were the ones who were ‘telling the truth.’ She absolutely hated Roosevelt.

Hard to know why; she was hardly an aristocrat! She hardly had any money, and

she certainly had no reason to be a Republican, but then … Oh, well! “So, she’s a model. She’s in Vogue.

And she’s an artist’s model: Steichen. At about the time she meets Cummings,

it’s likely she was also trying to achieve more in the theater. But suddenly she

moves from being a sort of career woman – because she was certainly building a

career – to being Cummings’s protector and supporter.”* And

I think no one has ever said it better than that. * * * After

accumulating these various facts and anecdotes, on March 21, a day before his

eighty-second birthday, I contacted Tony Ungaro for a follow-up interview. I asked

him to go over the story once more, and I began by asking what year he’d first

encountered Lillian. “In

1960,” he said, “I went to work for Heublein, Inc., and she was working in Central

Files, as a file clerk.” He offered her a ride home “within that year, and it

was just occasionally. She was living with her brother.” “Do

you know anything about the relationship between Lillian and Marion? Were they

close?” “Well,

they appeared together on the stage.” At this my ears perked up. This was new

information, and it might explain the nature of one particular image in Tony’s

collection in which the sisters are each heavily made up and wearing what appear

to be theatrical costumes. “I don’t think there was any problem between them,

frankly. Marion went her way, and Lillian went hers. And when Marion passed away

… Well, Marion’s husband had passed away first: E. E. Cummings. And of course,

Marion inherited everything. When Marion passed away, she left, to Lillian, the

income from his work. She continued to receive that. I think after Marion passed

away, E. E. Cummings’s daughter …” “The

last time we spoke, you said you heard that the daughter was a bit angry about

that.” “Somewhere

along the line, I’d heard that. I don’t know how true it was. But I can believe

she would have been a little disappointed, to say the least.” “The

sisters performed together on the stage? I don’t think anyone else is aware of

that. Did you have some kind of documentation in the boxes that they were in a

play together?” “Yes.” “There’s

also speculation that they were employed as showgirls for the Ziegfeld Follies.” “That

I don’t recall. I had a whole bunch of papers, and playbills, and things like

that, which I sent to the family. I don’t recall the names of the shows. Lillian

was quite attractive. In fact, she resembled, in my opinion, the actress Lillian

Gish.” After

summarizing Kennedy’s search for embarrassing “family secrets,” I asked Tony a

few pointed questions about the inner dynamics of the Morehouse clan. “I’m wondering

if you know anything about Lillian’s relationship with her parents.” “I

don’t think there were any problems between the parents and Marion; I didn’t see

any evidence of that. I saw no evidence of family problems, frankly.” “And

what about Lillian and the parents? Any estrangement there?” “Not

that I’m aware of, or saw at all. And let me tell you, I had a ton … the

lawyer sent me three boxes of material that he had left. And I didn’t see any

evidence of that, frankly.” “Do

you know anything about what led to the parents’ initial separation?” “I

know the mother was in a hospital in New York, and the father was trying to …

You know, holding down the apartment in Hartford. And those were some very difficult

times.” Although I was referring to the possibility of an estrangement between

1908 and 1918, I soon realized that Tony was actually referring to a later period,

“in the Thirties,” he said, during the Great Depression. “Difficult

financially?” “Financially,

right. And I don’t know what specific years all this occurred, but there was that.

It was difficult days. There was some correspondence between the parents. The

father was in Hartford. And the mother was in some hospital in New York. I think

it was a charity ward; I’m not sure. All this would have been in the letters,

which I don’t have anymore.” (One wonders if this could have been St. Vincent’s

Hospital, which always catered to the poor and which was conveniently located

near Patchin Place, at Greenwich and Seventh Avenue.) At

this point, we returned to the subject of Lillian. “When she worked at Heublein,

I had to go right by her street. So when she was stuck for a ride, she asked if

I’d drop her off. I said ‘Certainly, it’s right on my way.’ After she left Heublein,

I sent Christmas cards and things like that. Her brother was still alive, and

living with her. I think he worked part time, in a movie theater right up the

street.*

Other than these occasional communications, I never really saw her. Then I got

a letter from the probate court, saying I have ‘an interest,’ and blah-blah-blah.

And I said, ‘What the hell interest could I possibly have?’ [Laughs] You know,

this woman didn’t really have much; she worked as a clerk … as far as I knew.

She was living in this two- or three-family house. Then I called the lawyer, and

he told me she’d remembered me in her will, along with this doctor, and two women

who had helped her with her brother in later years. And she remembered everybody

in her will. So I called the doctor, and he said, “Yeah, it was kind of strange,

because when I told her I was moving out of state, she said, ‘Why’d you take me

out of the picture for, if you knew you were going to move?’ [Laughs] And I said,

‘That sounds like Lillian.’ “After

all was said and done, I think there was about four thousand dollars left to be

distributed. I was initially left ten grand. And I said to the lawyer: ‘I don’t

need the money. I want to make sure she has a proper stone and all that.’ He said,

‘That

was all taken care of.’ She’s buried with her parents at Mount Saint Benedict

Hospital, in Bloomfield. That’s where my parents are, and grandparents, and the

whole family. “I

had 1040s, tax forms, in that pile of papers, and I could see where Lillian was

getting the royalties from E. E. Cummings’s work. Twenty thousand dollars, or

something like that, a year. And that’s how she managed to build up her inheritance

if you will. But a lot of it went out for caretakers for her and her brother.

She didn’t die wealthy.” Tony

spoke with a palpable affection for Lillian and with a lingering fascination with

her past. “I’ll bet you regret not having spent more time with her while she was

alive,” I said, “and getting to know her better.” “Well,

yeah, in view of her history, which I had no knowledge of when I knew her at Heublein.

When I started going through those boxes, I was floored. It was amazing. Full

of photographic albums, pictures that went back easily into the 1800s. Which I

wasn’t going to throw away, and I had no use for. And I was … ‘What the hell am

I going to do with all this?’ My conscience wouldn’t let me destroy it, other

than the very personal letters between Marion’s mother and father. So I tracked

down relatives in Indiana, and I sent all that material to them. And what they

did with it, I have no idea. But there were all kind of playbills from the shows,

pictures of her in costume, and … oh!” “Pictures

of Lillian and Marion in costume?” “Yeah,

on the stage. I think Marion was also in some movie. A small part with Lionel

Barrymore. Whether she got credit for it or not on screen … But there was something;

she was in Hollywood. And there were some letters she wrote that were not too

kind to some people.” [Laughs] “Not

too kind to people in the film?” “No,

in the movie industry. Written to a friend or family; I can’t recall which. It’s

been a number of years now, you know? And there was something in there, I believe

it was a film with Lionel Barrymore, back in the Twenties.” As far as I know,

this is the first compelling evidence that Marion had appeared in a Hollywood

film. (Charles Norman, a friend of Cummings and Marion and the author of the authorized

biography, E. E. Cummings, says that Marion was in two films that were

shot in Long Island. But since Marion was the probable source of this information,

this must be taken with a grain of salt.* )

“She

was obviously a talented woman. Too bad you didn’t contact me fifteen years ago.

I would have had a lot more information, and I would have made it available to

you. What a book you could have written … You would have had a great time!” After

wishing Tony a Happy Birthday, he passed along the name and address of one of

Marion’s relatives in Indiana. “Maybe she can help you.” Thus,

the search for the elusive model, muse, and starlet continues. * * * Although this brief genealogical

foray into Marion’s distant past represents only a minor footnote to the work

completed by Richard Kennedy and Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno, perhaps it will

help future biographers to uncover more of the colorful history of the Marion

Morehouse family.

Documents and Photos:

Photographs

from the Tony Ungaro Collection:

|

• Anna (Shortell) Morehouse (left) and daughter Marion (right). If Marion was fifty years old here, the photo would be circa 1953, making her mother about seventy-three. This is the only known image of Marion with her mother, and, like most of the photos that follow, it has never before been made publicly available. |

| •

A young Marion Morehouse, her hair gathered

in an elegant up-sweep, wearing a black wool jacket trimmed in mink over a

bias-cut red silk dress, with draped wrap neckline and accessorized with

leather gloves and a jeweled bracelet. I have not yet identified the photographer,

although the style appears to be that of Steichen’s. Steichen usually shot in

black and white, but he began to experiment with color in the mid-1930s, utilizing

more of an informal, “snapshot” composition. Since color photographs first appeared

in 1935, Marion would have been at least thirty-two years old. |

| • Lillian Morehouse. (One of three photos that Tony Ungaro uploaded

to “Find-a-Grave.) |

| •

The only known image of Marion’s father, |

| •

Lillian Morehouse, in later years. |

| •

Marion’s brother, Benjamin W. Morehouse. |

| •

Marion’s mother, Anna Shortell, |

| • Left to right: Benjamin Morehouse, Jr; Anna (Shortell) Morehouse; Lillian Morehouse. (One of three photos that Tony Ungaro uploaded to “Find-a-Grave.) |

| •

The poet Edward Estlin Cummings, the lifelong partner of Marion Morehouse, in

front of a barn at Joy Farm, his New Hampshire retreat. The photo was taken by

Marion Morehouse. (Note the inscription: “E. E. Cummings 1939,” on top left.)

|

| •Lillian

Morehouse, her hair in a styled bob, modeling a satin dress with |

| •

Marion (left) and Lillian (right): The only known photo of the sisters together,

and perhaps the earliest extant image of Marion Morehouse. According to Tony Ungaro,

Lillian and Marion performed together on stage. This image appears to have been

professionally composed, and it may have been taken while they were working together. |

| •

An early photo of Lillian and her brother, Benjamin W. Morehouse. |

Lysistrata

Opening date: June 5, 1930. Closing date: January 1931.

Total Performances: 252.

Marion Morehouse: Second

Corinthian Woman.

Produced by Philadelphia

Theatre Association. Adapted by Gilbert Seldes. Choreographed by Doris Humphrey

and Charles Weidman. Staged by Norman Bel Geddes. Music by Leo Ornstein and Reinhold

Gliere.

44th Street Theatre, 216

W. 44th St., New York, NY.

Seats: 1465.

Built: 1912. Closed: 1945.

Demolished: 1945.

Mr. Moneypenny

Opening Date: October 17,

1928. Closing Date: December 1928.

Total Performances: 61.

Marion Morehouse: Iris; The

Dead Woman.

Comedy, written by Channing

Pollock. Directed by Richard Boleslavsky.

Liberty Theatre, 234 W. 42nd

St., New York, NY.

Seats: 1055.

Built: 1904. Closed: 1933.

The Saint

Drama, written by Stark Young.

Opening Date: October 11,

1924. Closing Date: October 1924.

Total Performances: 17.

Marion Morehouse: Daughters.

Greenwich Village Theatre

(later named the “Irish Theatre” in 1929), 7th Avenue South, near Christopher

Street, New York, NY.

Seats: 425

Built: 1917.

This Fine-Pretty World

Drama written by Percy MacKaye.

Opening Date: December 26,

1923. Closing Date: January 1924.

Total Performances: 33.

Marion Morehouse: Delphy

Boggs.

Neighborhood Playhouse, 466

Grand St., New York, NY.

Built: 1915. Demolished:

1927.

The Player Queen

Farce, written by William

Butler Yeats.

Opening Date: October 16,

1923. Closing Date: November 1923.

Total Performances: 49.

Marion Morehouse: Second

Countryman.

Neighborhood Playhouse,

466 Grand St., New York, NY.

Courtesy of the Playbill Vault and the Internet Broadway Database:

| •

The 44th Street Theatre, where Marion appeared in

Lysistrata. |

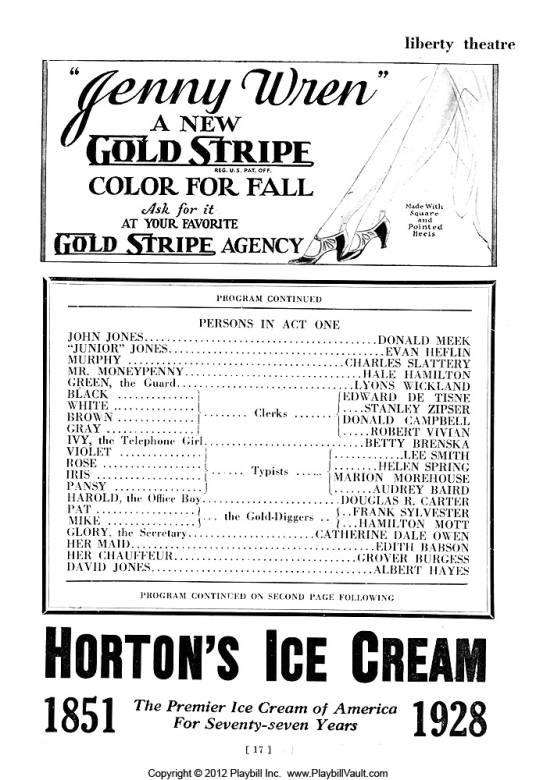

| •

A page from a 1928 Playbill for Mr.

Moneypenny,

which lists Marion in the role of “Iris.” |

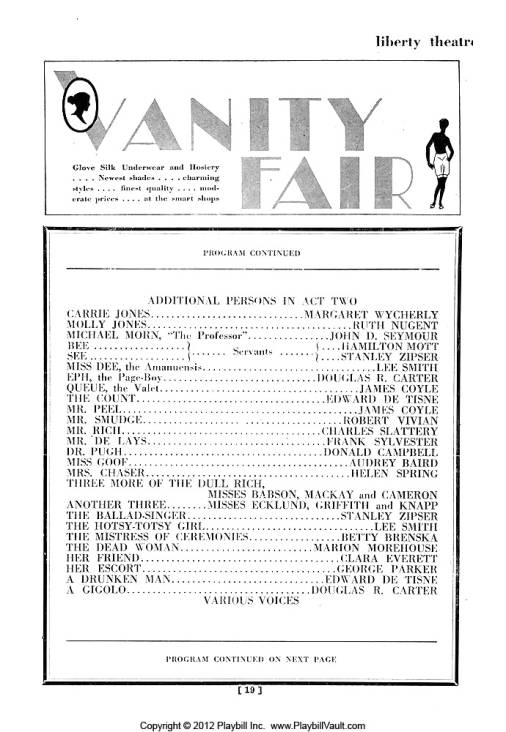

| •

In Act Two of Mr.

Moneypenny, Marion appears as “The Dead Woman.” |

|

•

The Liberty Theatre, which featured Marion in Mr.

Moneypenny. |

| • Playbill for Lucky, March 22, 1927, which lists Lillian as one of the “Showgirls.” |

| • The New Amsterdam Theatre (where Lillian appeared in Lucky) also hosted the Ziegfeld Follies. |

Musical, comedy, Broadway.

Opening date: March 22,

1927. Closing date: May 21, 1927.

Total Performances: 71.

Lillian Morehouse: Ensemble

performer.

Book by Otto Harbach. Music

by Jerome Kern. Musical Director: Gus Salzer. Music orchestrated by Robert Russell

Bennett. Lyrics by Otto Harbac. Staged by Hassard Short. Choreographed by David

Bennett. Ballets arranged by Albertina Rasch.

New Amsterdam Theatre, 214

West 42nd St., New York, NY.

Seats: 1747.

Built:

1903.

Earl Carroll’s Vanities

of 1925

Musical, revue, Broadway.

Opening date: July 6, 1925.

Closing date: December 27, 1925.

Total Performances: 199.

Lillian Morehouse: Ensemble

performer.

Produced

by Earl Carroll. Music by Clarence Gaskill.

Book by William A. Grew, et al.

Music interpreted by Ross Gorman. Musical

Director: Donald Voorhees. Staged by William

A. Grew.

Earl Carroll Theatre, 753 Seventh Ave. (West 50th St.), New York, NY.

Seats: 1025.

Built: 1922. Closed: 1939.

Demolished: 1990.

Earl Carroll’s Vanities

of 1924

Musical, revue, Broadway.

Opening date: September

10, 1924. Closing date: January 3, 1925.

Total Performances: 133.

Lillian Morehouse: Ensemble

performer.

Music Box Theatre (September

10, 1924 – November 1924),

239 W. 45th St., New York,

NY.

Seats: 1009.

Built: 1921.

Earl Carroll Theatre (November

10, 1924 – January 3, 1925)

(Thanks to the Internet

Broadway Database, the Playbill Vault, and the Internet Movie Database for the

information contained in these chronologies.)

____________________

*

*

Tobia Bezzola, “Lights Going All

Over the Place,” from William A. Ewing and Todd Brandow, Edward Steichen: In

High Fashion, The Condé Nast Years, 1923-1937 (W. W. Norton and Company, 2008),

p. 192. Published for the international exhibition of the same name that was organized

by the Foundation for the Exhibition of Photography, Minneapolis, and the Musée

de l’Elysée, Lausanne. The collection was exhibited in eight different museums

between 2007 and 2009, and it featured four photos of Marion Morehouse.

*

Harold Koda, The Model as

Muse: Embodying Fashion (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009), pp.

19-21. Published in conjunction with an eponymously titled exhibit at the Metropolitan

Museum of Art (May 6-August 9, 2000).

*

A more accurate

description would be: “not a famous model,” but the point is well taken.

Robin Muir, “Vogue’s Earliest Celebrity Models,” FirstFT magazine, September

24, 2010, ft.com.

*

The earliest Steichen photo of Marion that

Richard Kennedy seems to have been aware of is the one that appeared in Vogue

on October 15, 1925 (“Model Marion Morehouse wearing a dress by Lelong and Jewelry

by Black, Starr and Frost”). The portrait is reproduced in Richard Kennedy’s E.

E. Cummings Revisited (New York: Twayne Publishers, 1994), on page 112. In

the words of Sawyer-Lauçanno, the photos from this period “reveal an absolutely

stunning young woman, with large brown eyes, long dark hair, perfect full lips,

and a Roman nose. By the early 1930s, her career as a fashion model was well established

and she was in high demand.” E. E. Cummings, A Biography (Naperville, IL:

Sourcebooks, 2004), p. 363. In Dreams in the Mirror, Kennedy calls her

“one of the great beauties of her time,” noting her “long elliptical face,” “high

cheek bones,” “swanlike neck,” “delicately curved breasts.” Echoing Steichen,

Kennedy notes: “Her training in the theater helped her to become a renowned fashion

model, for she had the knack of adapting herself to the character of the clothes

that were chosen for her.” Kennedy, Dreams in the Mirror. A Biography of E.

E. Cummings (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 1980), p. 337.

*

Although

a marriage of seven years would have made Marion’s birth legitimate, Benjamin

and Anna were actually married for about six years at this time.

*

Kennedy,

“The Elusive Marion Morehouse,” Spring. The Journal of the E. E. Cummings Society

(Flushing, NY: E. E. Cummings Society, 1996), Number 5, p. 9.

*

Otto

Leo Morehouse was employed as a chauffeur and taxi driver during the Great Depression

(while his father was a janitor) and later as a clerk. He died three months before

Marion, in February 1969.

*

A

county clerk from South Bend informed me that crossing over the state line in

order to marry after a divorce was a common practice; otherwise, one might be

forced to wait up to two years to marry again within the state. Anna’s surname

appears here as “Shortelle.” Lillian Morehouse’s birth certificate says that Benjamin

worked as “shoeman” (sic). Most likely, the person gathering the information mistook

the (spoken) word “showman” for “shoe man.”

*

Since

the information contained in city directories is gathered during the year prior

to their publication, a listing in a “1904” directory actually reflects a person’s

residence and employment status in 1903.

*

“In

her social views, she posed as a ‘monarchist’ and an ‘aristocrat’ and often offered

her opinions with hauteur. Like many people lacking in educational background,

she enjoyed looking down on others – working-class people or people outside their

social circles – in order to elevate herself.” Kennedy, “The Elusive Marion Morehouse,”

p. 12.

*

Kennedy, Dreams,

p. 337. According to the Playbill

Archive, the play “Lysistrata” starred Hortense Alden (from the New York Theater

Guild), who made her Broadway debut as a teenager and who performed in fifteen

Broadway productions between 1919 and 1939. She would later appear in a 1964 episode

of the TV serial, The Doctors and the Nurses (1962-1965).

In 1941, Hortense married James T. Farrell, author of the Studs Lonigan

trilogy. For more on the production

of Lysistrata, see my “Partial Chronology of Marion Morehouse’s

Theatrical Work.”

*

Although neither Morehouse sister appears in the online Ziegfeld Follies

archive, Lillian’s name is listed in two of Earl Carroll’s Vanities productions,

which were Ziegfeld Follies-like musical revues. Carroll constructed his

own Broadway venue, The Earl Carroll Theatre, which in 1925 featured Eugene O’Neill’s

premier of “Desire Under the Elms.” Carroll’s theater on Seventh Avenue was purchased

by Ziegfeld in 1932 and renamed the Casino Theatre. It later hosted the Woolworth’s

Department store. It was demolished in 1990.

Steichen’s widow, Joanna Steichen, briefly

mentions Marion and Cummings in her book, Steichen’s Legacy: “Once, Steichen

suggested making a series of nude photographs. Morehouse agreed and posed wearing

only long black gloves and stockings. Later, Steichen heard that she had married.

To save her any possibility of future embarrassment, he destroyed the negatives

of the nude sitting. Then he learned that she had married the avant-garde bohemian

poet e. e. cummings, who, Steichen believed, would have relished the pictures.”

Steichen’s Legacy (New York: Knopf,

2000), p. 106. Thanks to Christopher Sawyer-Lauçanno for alerting me to

the fact that Steichen and Cummings were friends.

*

Edward

Steichen: In High Fashion, The Condé Nast Years, 1923-1937 contains many portraits

of dancers, actors, and actresses from the early Twenties, including one captioned

“Actress Mary Eaton from the Follies, 1923”: the same year that Steichen arrived

in the United States. Plate 33 features one of the earliest photos of Marion taken

by Steichen and is captioned “Model Marion Morehouse wearing an evening gown by

Chanel, 1924.” This gelatin silver print first appeared in the February 15, 1925

edition of Vogue.

According to author Nancy Hall-Duncan,

Marion “was first seen in Steichen’s photograph of November 1, 1924 for American

Vogue. Nancy Hall-Duncan, The History of Fashion Photography (New

York: Alpine Book Company, 1979), p. 54. Considered a classic in the field, this

catalog was published in conjunction with the History of Fashion Photography exhibit

produced by the author for the International Museum of Photography at the George

Eastman House in Rochester, New York. The exhibit also traveled to several other

museums in the United States.

*

Kennedy,

“The Elusive Marion Morehouse,” p. 9.

*

This

was the same conclusion reached by Cummings’s friend Charles Norman, who says,

“When she married Cummings, she put her career behind her.” Charles Norman, E.

E. Cummings: A Biography (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1967), p.

10. Norman was personally acquainted with Cummings from 1925 until his death in

1962.

*

According

to Benjamin Jr’s death certificate, before he retired he was employed at the Webster

Theater in Hartford. City directories list his occupation as “assistant manager.”

*

“She

appeared in two films, and I have heard that whenever she arrived on location,

in a Long Island studio, spectators and technicians ceased watching the stars

to watch her.” Charles Norman, E. E. Cummings, p. 10.

| This essay was also published in More Collected Couteau: Essays and Interviews (Dominantstar, 2016), along with an interview with MIT Professor Christopher Sawyer-Laucanno, the renowned biographer of E. E. Cummings. Available on amazon.

"Couteau's essays are often rhapsodic appreciations and evocations of the work under study, and are stuffed with both insights and joy." - James Dempsey, author of The Tortured Life of Scofield Thayer. From Publishers Weekly, BookLife: "Couteau's essays are informal, fervent, and well-versed examinations of the work or author at hand. At their best, they include fascinating insights into the significance of a writer like [Hubert] Selby.... The interviews are uniformly strong and include conversations with Michael Korda on T.E. Lawrence, Justin Kaplan on Walt Whitman, and Robert Roper on Vladimir Nabokov. Not all of them focus on literature: author Jeffrey Jackson covers the 1910 flood of Paris and why it's relatively forgotten, and Robert De Sena, in one of the best interviews, discusses his life as a gang member turned community activist. Couteau's passion and wealth of knowledge are obvious throughout the book ... and should appeal to many readers." From the Midwest Book Review: "The joy of reading Couteau's works lies as much in his penetrating, crystalline language as it does in the works or figures being examined, and so readers receive a wide-ranging treat that examines victims, vengeance, mortality and immortality through an inspection process that educates even those unfamiliar with the subject [...] Readers seeking not just a literary presentation but a lively analysis of selected wordsmiths and their lives and influences must add More Collected Couteau to their reading lists. It's a powerful presentation that offers much insight and food for thought, and which should find its way into many a college classroom as well." Available on amazon. Contact: rob_couteau@yahoo.com |

Since: 28 May 2015 | Copyright © 2017 Rob Couteau |

key words: South Bend Indiana Lillian Morehouse Edward Steichen E. E. Cummings Marion Morehouse